What happens when bears are relocated from parks? One bear traveled 1,000 miles back to her home in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

It’s summer and Gabrielle Cabral is suiting up for a late-night dive. She pulls on her wetsuit and fins, straps on her mask and oxygen tank, and backrolls off the gunwale of a boat moored over shallow coral reefs south of Miami.

“It’s fun,” she says of the upside down, disorienting freefall into the darkness below. Once the bubbles settle, she presses a deflate button on her suit and sinks to the bottom of the reef.

This is Cabral’s favorite part. “It’s so quiet and serene. The only thing you hear is your breath escaping in bubbles.”

Cabral is part of a team of divers working in Biscayne National Park, a pocket of paradise south of Miami and north of Key Largo, Florida. With 95% of its territory underwater, Biscayne is the largest marine park in the National Park System.

The park hosts more than a half-million visitors a year. Each one is called to these waters by a sense of wonder — snorkeling, vibrant colors, and the dynamic sea life coral reefs are known for.

The park protects a rare combination of marine and terrestrial life, none of which is more important, or at risk, than coral reefs. As climate change, disease, and marine debris conspire to devastate the coral, park rangers, scientists, and community partners are working hard to conserve the backbone of this fragile ecosystem.

"Safeguarding coral against such an onslaught of threats is a daunting task, and one that can't wait,” says Sara Murrill, national resources program senior manager at the National Park Foundation. “Private philanthropy provides much-needed resources to help protect vulnerable coral immediately, while we work towards mitigating longer term problems like climate change."

A coral reef is a diverse marine ecosystem built over time by a polyp animal called coral. The tiny, soft-bodied invertebrates with a stony skeleton are related to jellyfish and anemones. They use tentacles to capture plankton and feed on other food.

Stony corals capture calcium found in seawater and use it to build calcium carbonate skeletons. When many coral polyps live together, they form a colony. And when many colonies live together, they form a coral reef.

Some stony coral species found in Biscayne, like staghorn coral, elkhorn coral, and mountainous coral are listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, based on such threats as ocean warming, disease, ocean acidification, trophic effects of reef fishing, sedimentation, nutrients, sea-level rise, and predation.

Corals coexist in a symbiotic relationship with algae called zooxanthellae that live inside the polyps. The polyps offer a home in shallow water where algae can photosynthesize and provide the polyps with food and oxygen. Algae are also the source of the beautiful colors that coral are known for.

While coral reefs are beautiful in both their color and structural variety, the biodiversity they promote is even more important, sustaining thousands of species of plants and animals with food and shelter. Despite covering less than 1% of the ocean floor globally, coral reefs support 25% of all marine life.

Reefs also act as critical infrastructure for humans by establishing a buffer against storms that might otherwise batter coastal communities. According to some studies, healthy coral reefs absorb 97% of energy from storm waves and mitigate against billions of dollars of flood damage annually.

Coral reefs also underpin a multibillion-dollar South Florida economy. With more than 70,000 tourism and fishing jobs, coral is of vital economic and ecological importance. In simple terms, both a thriving economy and ecology depend on healthy fish populations, and healthy fish populations depend on healthy coral reefs.

Coral reefs thrive within a very narrow set of conditions. The slightest change to their environment can harm the delicate coral. Big changes can devastate it. If water temperatures are too warm, for example, zooxanthellae can produce toxins, which are harmful to corals. For self-preservation, the coral polyps must evict the zooxanthellae that they rely on. What remains is transparent coral tissue and white skeletons within. The coral is left with a “bleached” appearance.

When algae leaves, it takes with it the coral’s color, oxygen, and food source. If algae don’t return, the coral dies, leaving behind the calcium skeletal remains with a bleached-white appearance.

Such coral bleaching is increasing around the globe and, as ocean temperatures rise, it’s becoming more extreme and acute. Just last summer, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association observed unprecedentedly warm ocean temperatures around Florida that stressed, bleached, and killed coral.

In addition, more active troublemakers threaten fish populations living among the coral reefs. The invasive and carnivorous lionfish, for example, eat native fish that help to balance reef ecology, like algae-eating parrotfish that keep seaweed from choking the reef. It’s one more of the many challenges park rangers face today in Biscayne.

“There is value in describing all the aspects, so people understand the magnitude of threat the reefs are facing,” says Amanda Bourque, an ecologist with Biscayne National Park's Habitat Restoration Program. “It really is from every angle. It’s not just one issue.”

In addition to bleaching, coral in Biscayne is also under attack by a highly lethal disease first discovered off the coast of Florida near Miami in 2014. Since then, the disease has infected at least 22 species of reef-building coral across the entire length of the Florida Reef Tract.

The disease is exceedingly fast-moving and devastating. It appears as lesions on the surface of coral, which destroy soft tissue and can kill a colony within weeks.

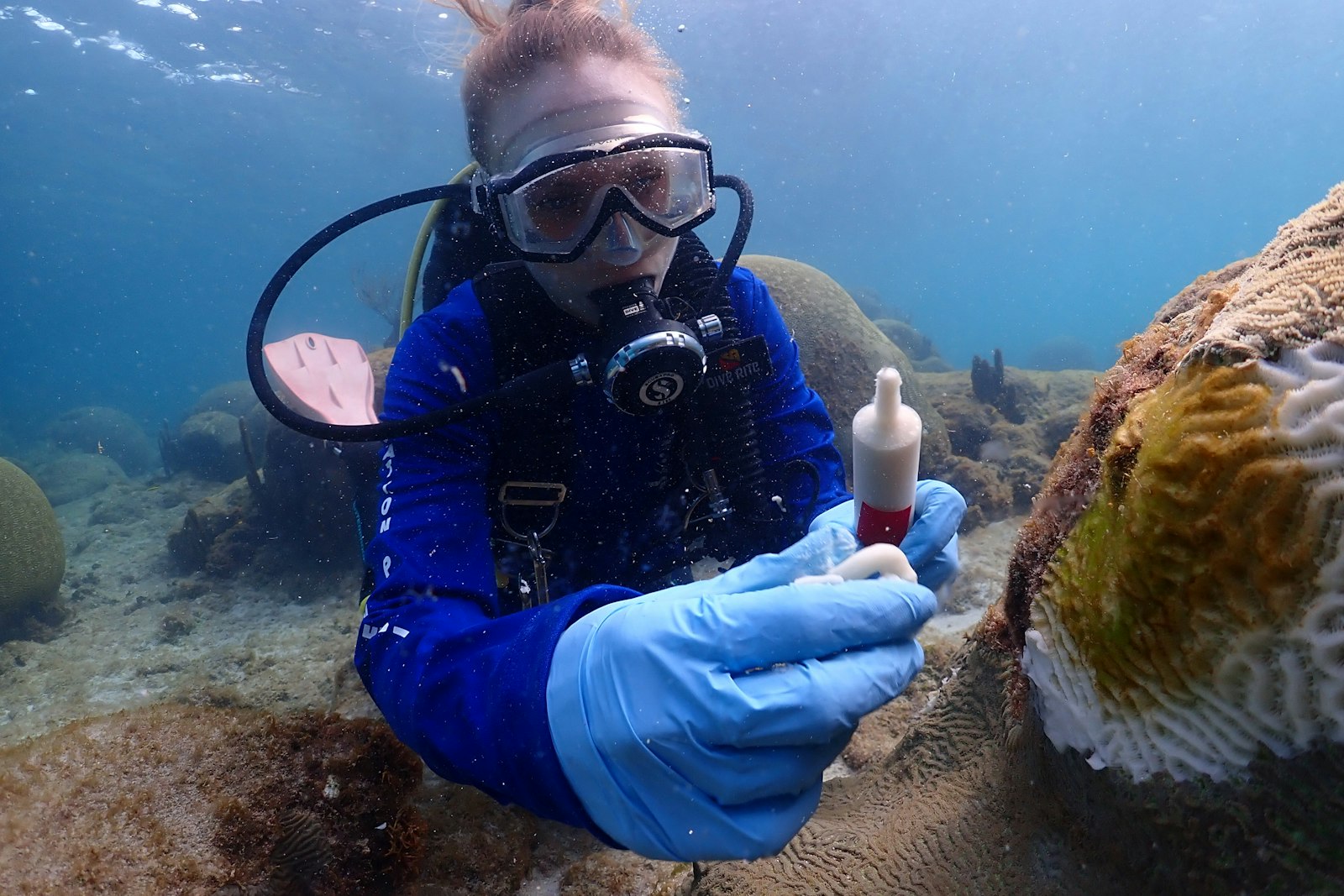

But park scientists like Cabral work fast too. Through regular dives, they perform check-ups on the coral colonies.

“We line up and swim next to each other to cover as much ground as we can,” she says. “Sometimes we swim in one direction then swim in another to see things from different angles and evaluate whether the disease is present.”

Cabral and the others tag coral and keep track of their health in a database that stores information like size, age, and photographs.

If they detect the disease, they treat it the same way your doctor might treat sickness—with antibiotics. They apply an amoxicillin paste to the infected area to stop the disease’s spread. This life-saving treatment is highly effective and means that coral hundreds of years old—including slow growing species that only grow 1-2 mm each year—have immediate protection.

The challenges don’t end there. In addition to bleaching, invasives, and disease, reefs in Biscayne are the ironic victims of the very fishing industry they uphold. Fishing and boating debris litters the water and reefs, and boat groundings cause physical damage to the reef.

“Tons of debris from fishing activity as well as ocean born debris from far away smothers coral and kills it,” says Bourque. “It’s also ugly and hurts tourism.”

Cleaning up the debris is done in scuba gear, which is labor intensive and slow. Divers carry several large mesh bags to collect debris from the ocean floor. Once filled, the bags are inflated and sent to the surface to be collected by teams on boats.

For the last three years, NPF has funded a crew of women military veteran divers. In just one year, they went on nine dives and in summer 2023, divers at Biscayne removed about 5,000 lbs of debris, including trap, fishing, and anchor lines.

Given all the challenges, what can be done to protect the delicate coral reefs and the vital ecosystems they support?

That’s precisely why Cabral is out for that night swim. She is here to collect gametes, the reproductive cells released by corals.

Corals are bound to the sea floor, after all, and can’t move around in search of mates. Many species of stony corals reproduce by releasing, or broadcasting, sperm and eggs in a synchronized spawning.

The release of gametes all at once is a tactic that ensures reproductive success. It increases the possibility for many different genetic combinations to form when gametes from different parent colonies combine in the water column. In such an at-risk environment, genetic diversity may be the secret to resilience, with new gene combinations that can help coral survive disease and the impacts of climate change.

It is one of the most spectacular events in nature, and Cabral is here to capture it, literally.

“Corals decide to spawn based on environmental cues,” she says. “A major cue is the full moon, usually in late July or early August. It’s our cue, too.”

Depending on the target coral species, a few days after the full moon, Cabral and other divers spend their nights capturing gametes. They use collector nets — conical tents made of fine mesh that are weighted at the bottom and buoyant at the top. At the narrow top end, there is a vial or jar that the gametes float into.

“It’s all arts and crafts down here because there are no tools for the sort of work we do,” she says.

Cabral turns off her dive light. In the pitch darkness, she can’t see her hands in front of her face. She waits and watches.

Tiny bright orange balls begin to bundle on the tips of the coral. The divers set the nets over the coral colony. Once the gametes are released, they float up to the net and into a collecting jar. The rest of the gametes wander adrift in the current, combine, form baby corals called planulae, and float for several days until they find a hard surface to settle on.

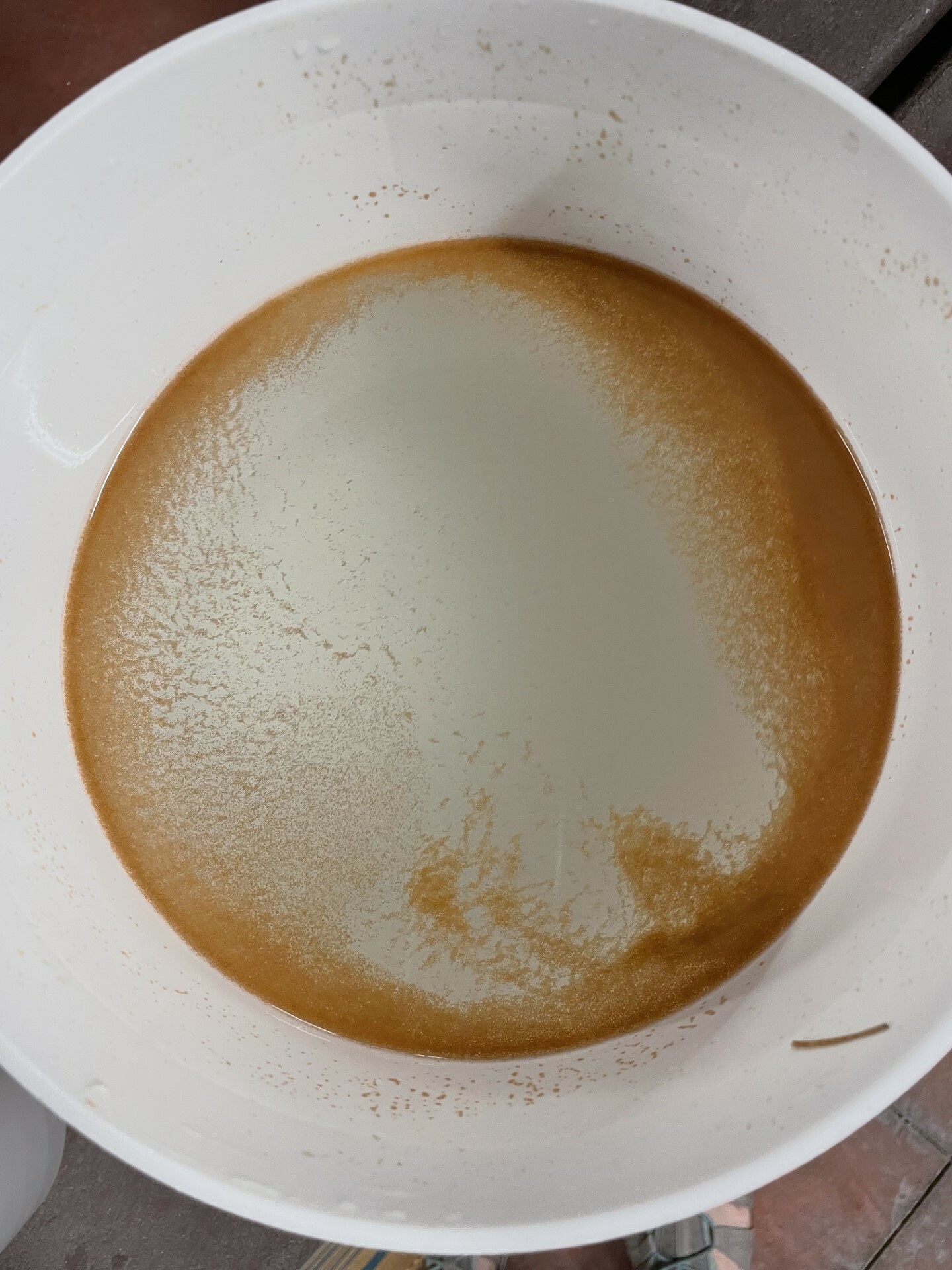

Back on the shore, it’s more arts and crafts. Cabral and the team place the gametes in paint buckets. Once fertilized, they’re reared in seawater tanks, monitored for several weeks, and then transported to a land-based nursery with one of their partner organizations until they're big enough to be outplanted back to park reefs, where they will bolster coral populations and diversity.

Biscayne works with multiple partners on propagating corals, including the Mote Marine Laboratory, the Florida Aquarium, the University of Miami, and SECORE International.“Thousands and thousands of new, unique corals can come out of one of those spawning nights,” says Cabral.

Work like this is helping scientists and reef managers understand how reproductive behavior and success are affected in corals that are diseased and bleached.

Disease treatment, marine debris clean up, gamete collection, and outplanting of nursery-reared coral are all ways National Park Foundation grants help to protect and restore coral reefs. It all relies on dive equipment, dedicated and hardy personnel, and a network of community partners working together to save a priceless resource.

"When most people think of national parks, they think of the more popular land-based road trip destinations,” says Murrill. “But 20 percent of all national park sites contain an ocean, coast, or lakeshore. There are 10 parks in the National Park System that contain unique coral reef ecosystems, offering visitors the chance to explore magnificent underwater wonders. These reefs were the reason some of these national parks were established to begin with, making our work to save the coral all the more important."

NPF’s Wildlife and Habitat Conservation programs protect and restore coral at national parks throughout the country. In addition to Biscayne, efforts are underway at four national parks in the Caribbean — Virgin Islands National Park, Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve, and Buck Island Reef National Monument.

Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease impacts more than half of all coral species in these Caribbean parks, threatening an already imperiled resource. In some places, coral has declined by 90% in the last 30-50 years. With the help of NPF funding, the National Park Service (NPS) is partnering with both the University of the Virgin Islands to administer disease treatment and with The Nature Conservancy on coral propagation and outplanting for restoration in in the Caribbean.

Coral conservation efforts in Florida and the Caribbean are all part of a broader NPS Coral Reef Resource Stewardship Strategy, a recently finalized comprehensive plan that will help all of the NPS Southeast parks with coral reefs to share expertise, prioritize stewardship needs, and leverage efforts across the region.

Bourque sees reason for hope in the coral species that survived mass bleaching and disease.

"Something about them makes them more resilient,” she says. “But when you lose genetic diversity, you lose resilience. If a new disease comes along, they might not survive that one. Diversity equals resilience. That’s why we’re working so hard to preserve coral diversity while we still can.”

This coral restoration work was made possible in part by the National Park Foundation through generous funding provided by donors like Publix Super Markets.

What happens when bears are relocated from parks? One bear traveled 1,000 miles back to her home in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

NPF funded research is helping track great white sharks, protecting the species, and enabling public safety officials to use science to educate the public on the risk of recreating in the waters off Cape Cod National Seashore.