Park Rangers, Archeologists, and Community Partners Work to Restore Trails in Hawaiʻi.

Tracking bears in the Great Smokies and beyond is helping park scientists discover the fates of relocated bears.

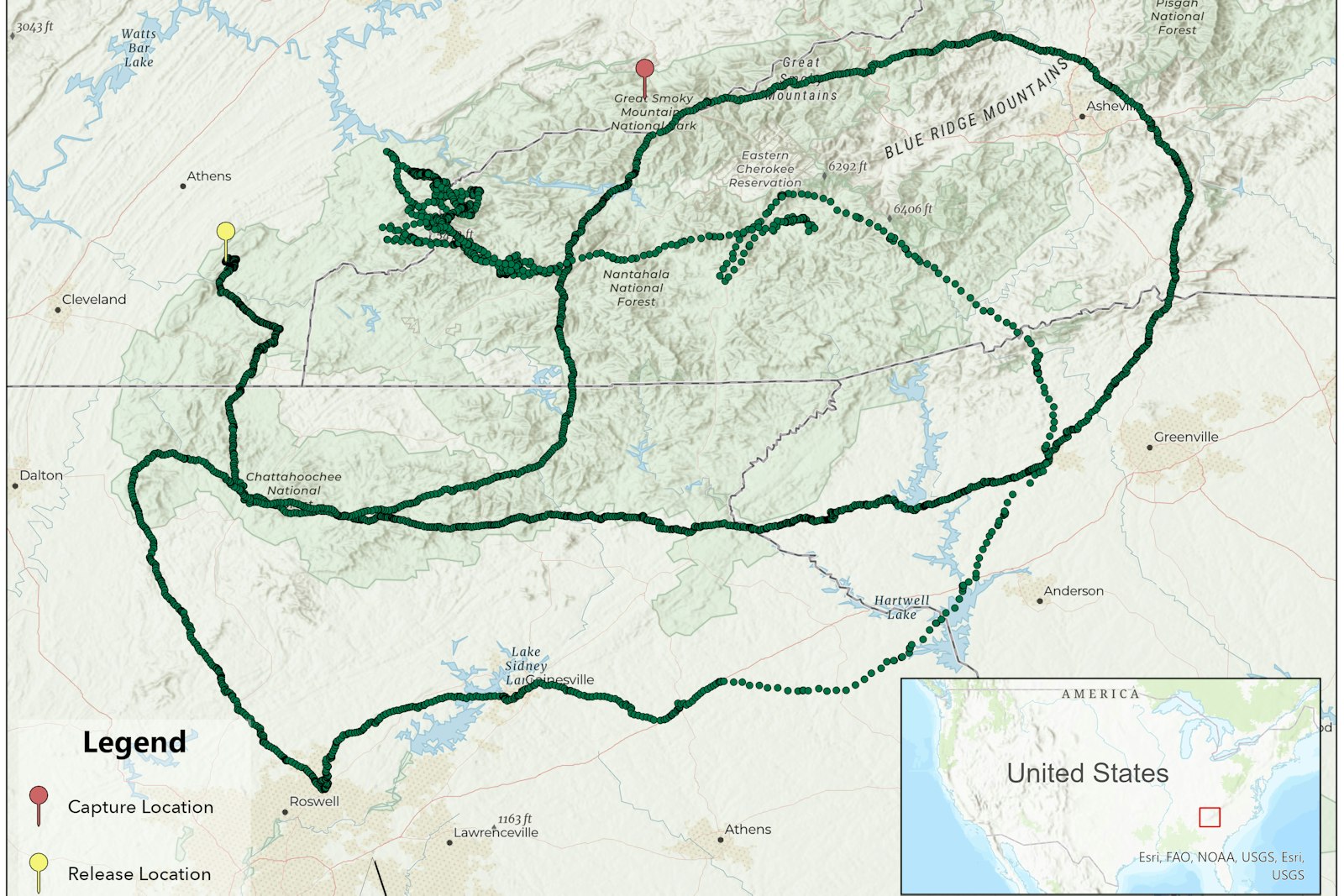

Bill Stiver hovers over his computer screen, zooming in, moving his cursor around, watching with excitement. His monitor shows hundreds of coordinate points on a map connected by meandering lines over a green forest background.

The coordinates show the movements of a handful of black bears in the areas surrounding Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Stiver, the park’s supervisory wildlife biologist, is part of a groundbreaking research project to understand the movements and fates of American black bears relocated from the park to mitigate potential human-bear conflicts.

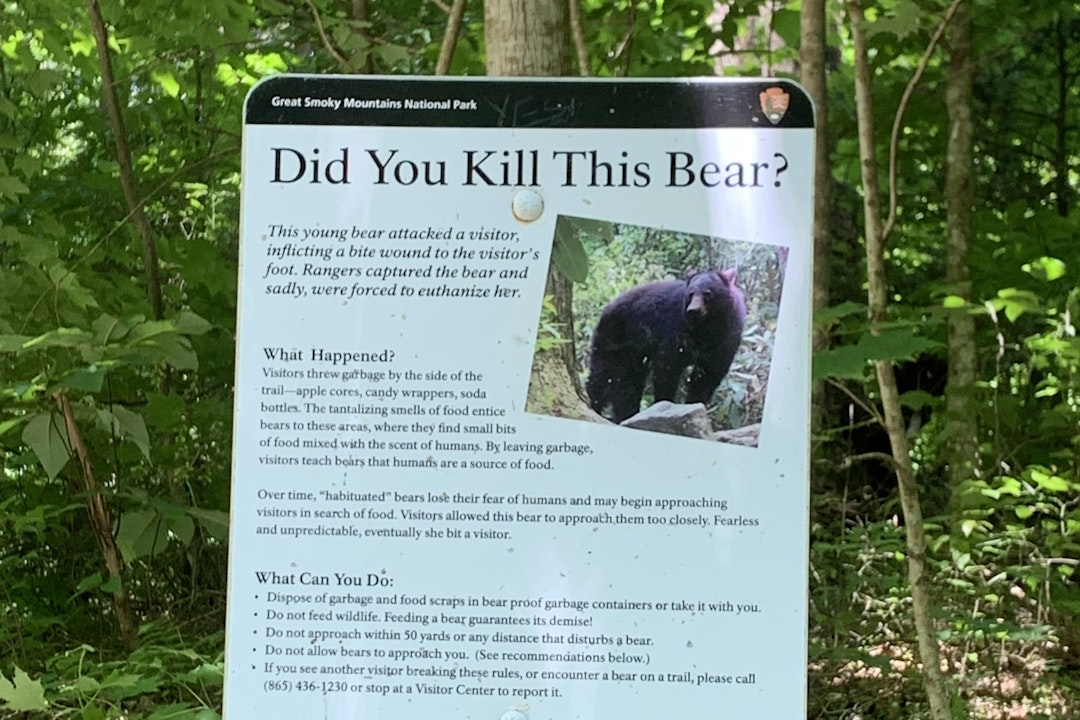

When a bear becomes accustomed to visiting developed areas of the park in search of human food or garbage and grows bold, park rangers must resort to capturing that bear and moving it elsewhere outside the park before it becomes a threat to human safety. While that’s been the practice for decades, for the most part it wasn’t known what happened to most of those bears: where they went, whether they caused conflicts elsewhere, or how long they lived.

With support from the National Park Foundation (NPF) and in collaboration with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the University of Tennessee, Stiver and the research team are using GPS tracking technology to answer those questions – questions Stiver has wondered about since his 1989 graduate work at the park studying relocated bears.

Their new findings – that relocated bears often die a few months after being moved – emphasize that the best way to protect bears is for people to live responsibly with them and prevent the escalation of behavior that may lead to a bear having to be relocated. And tracking the relocated bears has been eye-opening – one female traversed some 1,000 miles across four states during a six-month journey that ultimately brought her back to a den outside the park.

“The take-home message of all of this is if we really want to protect bears, we’ve got to prevent them from getting our food and garbage so that managers like myself aren’t in the position where we may or may not have to move a bear,” Stiver says. “It’s really an education thing. I’m trying to use the science to educate people.”

The Smokies are chock full of black bears. An estimated 1,900 bears call Great Smoky Mountains National Park home, amounting to about two bears per square mile. The park offers the largest protected habitat in the eastern United States where black bears can live in wild and natural surroundings.

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is also the most heavily visited national park. For the last decade, between 10 and 14 million people have visited the park each year.

For the most part, bears and people coexist. Bears go about eating berries and nuts, sometimes insects and animal carrion. They mate in the summer and sleep in dens in the winter. Most bears in the park are afraid of people.

But sometimes, the presence of people can cause problems for bears, mostly when people leave out food or garbage. With their keen sense of smell, bears can identify scents from very long distances: anything from leftover picnic food or snacks spilled on a trail to birdseed in a backyard bird feeder can easily attract black bears. Combined with their biological need to store fat reserves for winter, bears’ sensitive noses, curiosity, and intelligence can lead them to those human food sources.

Park managers keep careful watch on what happens next. A bear may first enter a picnic area, campground, or someone’s yard at night to get some scraps, and over time, that bear may become bolder, less scared of humans, and more eager for that food. The bear, a quick learner, may start coming to picnic areas or campgrounds during the day and might try to take over a picnic table or get into a tent. The escalation of that behavior can pose a threat to human property or safety.

“If we allow bears to get our garbage, they know to come to us, and if we allow that to continue over time, they become bolder and bolder and bolder,” Stiver says. “By allowing bears to get that food and garbage, even if it’s a little bit at night, you’re starting that process, just like training your dog, and we don’t want that process to start.”

Park biologists actively deter bears that show any early signs of food-conditioning. If a bear is hanging out in a developed area of the park looking for food, managers want it to be a negative experience for the bear, not a reward. They may trap that bear, tranquilize it, take various measurements for data collection, then release it back into the park– not painful, but an experience that’s meant to deter the bear from that same behavior.

Biologists tracked around 50 relocated bears to follow their daily movements and fates. When a bear is outside the park, its GPS collar consistently transmits location data, allowing precise understanding of where the bear is and what it’s doing.

The findings have been “eye-opening,” according to Stiver. Most of the relocated bears (about two-thirds, per preliminary data) die within four months, killed either by cars, legal hunting, or landowners after the bears caused property damage. (These are not yet published final results; rather, preliminary observations based on the data collected.)

Bear relocation does not seem to be the happily ever after solution that people typically imagine, explains Kristin Botzet, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville graduate student lead on the project, who is transitioning now from fieldwork to data analysis and writing for her masters thesis and a journal article about the research.

“People think we’re going to relocate these bears and that they’re going to live their days out in the forest and not get into further conflict. But I think what the public needs to recognize is, that’s kind of an out of sight, out of mind mentality, and it potentially dumps the problem on someone else to deal with,” Botzet says.

The three-year study, wrapping up in late 2023, has also illuminated surprising movement trends. Bears aren’t staying put where they’re relocated; in fact, some bears have wandered hundreds of miles.

“The whole idea behind moving them from Point A to Point B was hopefully they would stay at Point B. That doesn’t happen. I think we’ve only had a few bears that stayed any length of time,” Stiver says. “Some of them are finding their way back, but some of them are really moving all over the place. That’s been very eye-opening how far these animals will travel when you move them.”

One such bear, Bear 609, so called for her collar ID number, gained national and international media attention for her shocking set of movements. After displaying increasingly bold and food-conditioning behavior at a backcountry site in the park, officials chose to capture the five-year old bear, fit her with a GPS collar, and relocate her 60 miles from Great Smoky Mountains National Park to southern Cherokee National Forest in eastern Tennessee.

Right away, she was on the move, heading south into northern Georgia, then South Carolina, North Carolina, and eventually back into Tennessee and passing through the park. She continued on again through those same states and eventually denned about 25 miles from where she was originally released six months prior.

During her 1,000-mile journey, she swam across nine bodies of water in multiple states, crossed 33 major roads, was hit by a car and survived, ventured through the Atlanta metro area, ate from a dumpster outside a steakhouse, tried to get into a shopping mall, and more, per Botzet’s analysis based on the GPS collar data.

Seeing in detail the movements of 609 and other bears was a highlight of the project and informative in terms of revealing just how much bears move across the landscape. Previous research based on older technology sketched a much rougher picture of bear movements: when Stiver started his research, they’d typically only know a bear’s fate and location if it was killed and its physical ear tag got returned; more recently, radio signals could detect locations more regularly but not as precisely; now, with GPS collars, exact locations can be identified multiple times an hour and bears’ ranges, den habits, and other movements are much clearer.

This project has been Stiver’s favorite over his 30-plus year career in the Smokies and he believes it’s “rewriting the science” in terms of what’s known about black bears and their movements.

The park’s relocation research has broad implications for local communities, park visitors, and biologists that manage human-bear conflicts. Because relocation often doesn’t end well for bears, the park and partners are exploring strategies and communications to protect bears.

It’s important for park visitors to be “BearWise,” park staff and local advocates say.

The BearWise® program, run by North American bear biologists, shares consistent messaging about coexisting with bears in bear country, including key tips for living responsibly with bears and preventing human-bear conflicts at home and outdoors such as to never feed or approach bears and secure any attractants.

“If we really care about the bears, then we need to do stuff on the front end to prevent human-bear conflicts,” Stiver says. “This research will be a big catalyst for educating people on being responsible with their food and garbage and birdfeeders and all that kind of stuff.”

“Seeing a black bear for the first time is a milestone memory for many visitors to Great Smoky Mountains National Park,” says Friends of the Smokies President Dana Soehn. “We want these experiences to be safe for bears and people. Supporting BearWise behaviors both inside and outside the park is one of the proud ways that the Friends works to protect bears.”

A previous research project at the Smokies found that 90% of male bears and 50% of female bears that lived inside the park sometimes went outside the park and into surrounding communities. So even if the park is managing food, garbage, and human-bear relations perfectly, if that’s not happening outside park boundaries, then a bear could go out, eat garbage from a dumpster, and bring that behavior back to a campground, causing problems inside the park.

“It becomes really important to work with our partners and work with our neighbors,” Stiver says.

Stiver, Botzet, and partners like Friends of Great Smoky Mountains National Park are committed to that work. Park staff work hard to communicate bear safety behavior to their millions of visitors; in between fieldwork and data analysis, Botzet teaches school groups in the Smokies about BearWise and her research; Friends of the Smokies funds a number of bear protection efforts in the park such as annual support for GPS tracking collars, backcountry food storage systems, and wildlife staffing support. The team hopes their novel research findings will further inspire visitors and neighbors to do what they can to help protect the region’s iconic bears.

The National Park Foundation would like to acknowledge and thank the following partners for supporting our mission to protect and enhance America's national parks for present and future generations: The Coca-Cola Company, L.L.Bean, Nature Valley, Subaru of America, Union Pacific Railroad, adidas TERREX, American Airlines, Arconic Foundation, Asset Marketing Services, BarkBox, Bush Brothers and Company, Carhartt, Chick-fil-A, Inc., The Coca-Cola Foundation, Columbia Sportswear, EVOLVE Plant-Based Protein, Expedia, Free People, GE Lighting, a Savant company, General Motors, goodr, H3 Sportgear, Headspace, Harland Clarke, J.Crew, Kinder Joy, Kleenex®, Kohl’s, Lenny & Larry’s, Maverik, Michelob ULTRA Pure Gold, Melissa & Doug, Mutual of Omaha Foundation, Niantic, Pendleton Woolen Mills, Publix Super Markets, REI Co-op, Sierra, Stericycle, Sun Outdoors, Superior Plus Propane, Tango Card, Tito’s Handmade Vodka, Tom’s of Maine, Winnebago Industries, and Winnebago Industries Foundation.

Park Rangers, Archeologists, and Community Partners Work to Restore Trails in Hawaiʻi.

Park rangers, scientists, and divers are working to protect coral reefs in South Florida.