Preserving Black History in National Parks

.

.

National parks connect us to nature and so much more. Parks tell the story of who we are—our history and heritage, our moments of triumph and our ongoing struggles.

The National Park Foundation (NPF) is dedicated to supporting parks across the country, elevating the rich diversity of stories that offer each of us the opportunity to experience a sense of wonder, appreciation and a deeper connection to nature and the history and heritage we share.

In collaboration with the National Park Service, the park partner community, and with the support of donors, including philanthropist Robert F. Smith and the Fund II Foundation, the National Park Foundation is helping to ensure everyone can see themselves in parks, and truly feel welcome across the landscapes and historical sites that belong to all of us.

Thanks to Mr. Smith’s ongoing commitment and generous contribution to the National Park Foundation’s African American Experience Fund, Black history is being preserved, honored, and celebrated in our national parks.

Will Shafroth (WS): Robert, let’s start at the beginning with your own early experiences in the national parks. How did visiting the national parks help shape your childhood?

Robert F. Smith (RS): As a child, I remember listening to my grandmother tell stories about her summer visits to Lincoln Hills in Colorado in the 1920s. African Americans had long been barred from access to hotels and other destinations, so Lincoln Hills was established as a destination for our community to go and find peace and quiet in fellowship and family. Over the years, countless Black Americans like Billy Eckstine, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Zora Hurston, and Langston Hughes all spent time at Lincoln Hills.

I grew up in Denver in the early 1970s as schools were in the process of desegregation. In the summer of 1971, my father—who was working on his PhD at the time decided we would go on a family trip to the Great Sand Dunes, Mesa Verde, and Dinosaur National Monument in Colorado. I remember wondering why we were about to trek around Colorado on this trip. But it was on that trip when I learned about my family history.

Over those two weeks, as we drove through Colorado in a smoke-filled car—windows up—my father told stories of how our family got to Colorado four generations ago.

While the parks were the destination on that trip, the magic was in the journey—bringing our family together for 14 days, talking, getting to know our ancestors and history. Of all our family vacations, this is the one I remember most.

WS: What do the national parks mean to you now?

RS: The national parks hold a special place not just in my family’s history, but in the history of our nation. These sites are where many of our ancestors and leaders spent time, lived, thrived, fought, and gathered. On a personal level, I’ve always felt a calling to preserve these spaces and share their stories with my community.

I’ve been honored to work with the Fund II Foundation to contribute to the preservation and elevation of the African American experience at historic sites that are a part of the National Park System. These include the birth and life homes of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Atlanta and the Pullman National Monument in Chicago.

Both my father and grandfather—both named William Smith—served on the railroad as waiters and porters. The story of Pullman Porters and how they built a community within Chicago and helped build the Black middle class in America is a story of hard work and progress. It is both an honor and duty for me to help preserve these places and share these stories.

I also appreciate that not everyone can visit so many of our parks and so we need to expand our use of digital technology to make them more accessible to all. My children consume much of their knowledge and information digitally. And while preserving and restoring national park sites is crucial, we must also enable the digital experience to communicate the rich histories of these spaces to the next generation.

WS: On that note, let’s dig a little deeper into what preservation of these historic places looks like. The Fund II Foundation is actively supporting more than a dozen projects across the National Park System through the National Park Foundation’s African American Experience Fund. Why is preserving and honoring Black History in our national parks so important?

RS: As I’ve mentioned, I’ve had the great pleasure of working with both the National Park Foundation and Fund II Foundation in the preservation and storytelling of some of our country’s most important historic sites, including the homes of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Carter G. Woodson, and Booker T. Washington, as well as the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail. These spaces provide a link to our past, creating space for intergenerational conversations about who we are and who we hope to become as members of our communities.

In 2019, the National Park Foundation and I worked together to purchase the birth and life homes of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and then turning these properties over to the National Park Service for their perpetual stewardship and interpretation. In addition to supporting the acquisition of the birth and life homes, through Fund II Foundation we were also able to enact emergency repairs to the family home and digitization of family home assets and oral histories critical for research and future digital storytelling.

My mother took me to the March on Washington when I was six months old, and while I may not remember attending, the lessons of Dr. King were ever-present within our home and community throughout my childhood. As a father, these lessons have been something I have passed down to my own children.

In purchasing Dr. King’s birth and life homes, it was crucial that the King family and the National Park Service remained at the core of our preservation strategy. Following the purchase of the homes, the National Park Foundation transferred its care to the National Park Service to be incorporated into the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta so that others may share in the memories and learn the lessons my parents shared with me all those years ago.

WS: Some of your more recent philanthropic initiatives are focused on increasing people’s access to the outdoors, especially for those in the African American community. Tell me more.

RS: Throughout the majority of our history, Black Americans have been excluded from accessing recreational spaces, whether through policies barring access or via discriminatory practices like redlining which physically isolate our communities from these destinations and services. This despite, in many cases, Black workers helped to build them. Today, much of my philanthropic focus centers around sharing the rich history of these landmarks with our youth and providing them access to outdoor spaces and educational opportunities to show how all our experiences are inextricably linked.

It’s been an honor to be involved with the Lincoln Hills Cares program, a program I co-founded in Denver, Colorado, to preserve the Lincoln Hills ranch and develop the next generation of young leaders through outdoor recreation and education, cultural history exploration, and workforce advancement. Every summer during this program, we see these young people—inner-city kids and mountain kids with different backgrounds—working and playing together. National parks can also provide a useful context to bring together diverse youth who can share experiences in the outdoors and become stronger leaders.

On a personal level, I’ve shared my experiences and love of the natural world with my family. They have been able to experience the wilderness in relative peace and safety and these experiences will, I hope, resonate with them throughout their lives just as my national parks experiences with my parents resonate with me even now.

In the broader sense, I’m lucky to be able to try to help other families in communities across the country to expand access to these experiences. And so, where I’ve been able to, I’ve contributed to a number of projects, including the renovation of an outdoor performing arts venue in Harlem, as part of Denny Farrell Riverbank State Park. In Austin, I support The Trail Foundation, which is preserving accessible pathways where everyone can find a moment of tranquility in the heart of the city.

And on a larger scale, it’s been my honor to help the National Park Foundation preserve national treasures that are part of African American history.

WS: What can we, as community members, do to expand access to outdoor learning and experiences for us, our children, and others?

RS: As members of the human race, we must come together to ensure the natural gifts of this earth will be available for generations to come. To accomplish this, we must address not only issues of green spaces, but of racism and inequality, and lead by example, so that the next generation of leaders can become the environmental stewards that our planet needs.

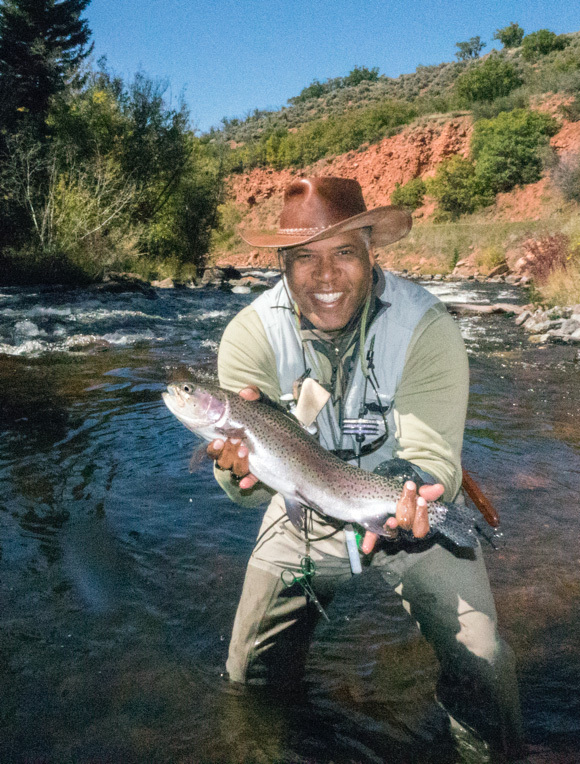

ALL children must have opportunities to experience nature and gain an appreciation for the clean water, fresh air, animals, and plants we hope to preserve—and do it in an environment where they feel safe and welcome. And we have to show kids that nature can be fun and fascinating. We can all do that by supporting programs that teach kids about the important interconnectedness of the natural world, climate change, and through outdoor recreational experiences like hiking, camping and fishing. Our national parks’ educational programs are an important part of ensuring future stewardship, as is our partnership through internXL1 to support more opportunities for people to experience careers with parks while providing the National Park Service with qualified, diverse interns to train the future stewards of these sites.

And I’d like to call out the work being done to steward and share our diverse history and culture. Additions to the National Park Service’s outstanding catalog of historic destinations have grown dramatically over the last 20 years. We now have the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park in Maryland, the Pullman National Monument in Chicago and the homes of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as part of a sacred network of historic spaces that educate and provide space for reflection.

WS: Now to the future. Describe what national parks might potentially look like in another 50 or 100 years. What should they provide for us all?

RS: Technology is our future, that’s a fact. The importance of digitally preserving the expression of our culture is critically important for all conservation and cultural institutions. I’ve had a number of conversations with Lonnie G. Bunch, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, over the years about how we must keep museums from becoming temples, and how we can make sure that they are alive in the consciousness of the public. And, for me, that means expanding the use of digital technology to ensure that we physical record and provide public access to those records.

Right now, thanks to this work, people have access to many digital archives, audio tours, online video tours and interactive exhibitions. Examples of all of these can be found at institutions such as the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the National Park Service sites. In the future, as virtual reality software and hardware improve, we will be visiting and experiencing our institutions without ever setting foot there. The groundwork is being laid now for what we will see and have access to in the future. For too long, the questions of what is worth preserving and what constitutes our history have not been examined through an inclusive lens. That is changing.

But to answer the last part of your question. I think what national parks should provide all of us is an education about ourselves and who we are as a people. The parks contain stories about what America is, and what it was. And that connects people no matter their socio-economic standing, their gender or perceived ethnicity. The parks show us a way forward by revealing our collective past.

WS: Robert, your partnership with the National Park Foundation and your tremendous generosity is making a real impact in national parks. As you look at the year ahead, what is the most meaningful thing we can do together to support national parks and connect people to them?

RS: When the United States Congress passed the original legislation to create our national parks back in 1916, the stated goal was to "conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein." And while the primary purpose of the parks is certainly to preserve our environment, I often think about how these monuments to nature are also monuments to our collective soul as a nation. National parks are blind to race or background and indifferent to politics. Parks are a place where "I" becomes "We." The best way to support national parks is to reaffirm to ourselves and each other that the majestic beauty of America can be found in our rivers and mountains, as well as in our ideals and our hearts. When we "find our park," we find common ground. And that's never been more important.

WS: Robert, thank you for your outstanding partnership and leadership on behalf of America’s national parks.

[1] The National Park Foundation partners with the Fund II Foundation, National Park Service, and Greening Youth Foundation on the internXL program.