.

.

In summer 2022, NPF supported a project at Petrified Forest National Park to manage prairie dog communities. Park staff partnered with nonprofit group Habitat Harmony, in Flagstaff, Arizona, and together they translocated 100 Gunnison’s prairie dogs (cynomys gunnisoni) from a construction site in Flagstaff, Arizona to a designated release site within the park. Providing a new home to displaced prairie dogs is one part of the park’s effort to boost prairie dog numbers in the park, combating region-wide population declines due to human activities, climate change, and plague outbreaks. The translocated prairie dogs were “soft released” into an artificial colony site near two other prairie dog colonies in the park – with the hope they would eventually disburse to the natural colonies. After the release, both nearby natural colonies of prairie dogs saw increased activity – a great sign!

The Project

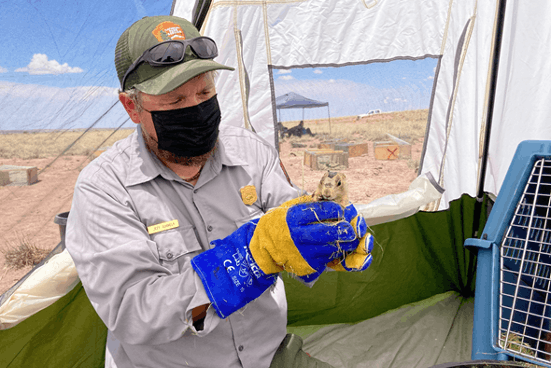

For several weeks before the translocation, park biologists were planning and constructing an artificial release colony while Habitat Harmony worked hard at the capture site. Supplies for the project were provided, in part, by the Petrified Forest Museum Association (PFMA), a nonprofit that supports park efforts by operating bookstores in the park. The release occurred across two days and involved 11 volunteers, including members of the Navajo Conservation Crew, Habitat Harmony, PFMA, and on- and off-duty park employees. Prairie dogs were transported from a Flagstaff construction site to the park, where the prairie dogs were processed and released into the artificial colony. If they had not been translocated, the prairie dogs’ colony would have otherwise been bulldozed over. Processing included tagging the prairie dogs’ ears, sampling any fleas for plague testing, and partially dying their fur so scientists would be able to spot the newly translocated prairie dogs from afar.

The prairie dogs were released in family groups, with up to eight put into one artificial burrow. The artificial colony was built using black tubing to lead the prairie dogs down to an underground chamber – a 20-gallon bucket turned upside down with some hay. A mesh cage was kept over the entrance tunnel for a week, providing a “soft release,” giving the prairie dog families protection from predators and time to acclimate to their new colony, thereby increasing the chance of staying and surviving in the new location. After the prairie dogs were released into the artificial colony, volunteers for the project came back to provide temporary supplemental feeding, necessary with the “soft release” procedure, and eventually removed the temporary mesh cages. From there, the prairie dogs were free to explore their new surroundings and dig their own burrows.

Gunnison's Prairie Dogs - A Keystone Species

So why are these little critters so important? Prairie dogs in general are unique to North America, and are a keystone species to the grasslands they live in. Gunnison’s prairie dogs, such as those translocated in this project, are one of five prairie dog species. Native to the four corners region, they live in smaller, less concentrated colonies than the other species and hibernate through the winters. In the grasslands, the prairie dogs are important ecosystem drivers, consuming and spreading specific plants, contributing to soil turnover and supporting water absorption with their burrows, as well as providing habitat and cover for snakes and burrowing owls.

Gunnison’s prairie dogs have numerous predators, including snakes, badgers, hawks, eagles, coyotes, and importantly, the black-footed ferret (mustela nigripes). With so many predators from land, air, or underground developing numerous hunting styles, prairie dogs have developed a warning “bark” to communicate complex ideas to colony members – biologists think that they can differentiate between species of snakes or birds, direction and speed of the threat, and maybe even colors. The most important predator is the black-footed ferret. One of North America’s most endangered mammals, it has been rated as extinct twice in the past century because their populations were so small. Thanks to repopulation and reintroduction efforts, there are now 1500 adult black-footed ferrets in the wild. Petrified Forest National Park has been marked as another potential reintroduction site for the species, but such an effort depends upon the park’s population of Gunnison prairie dogs, since they make up 90% of the black-footed ferret’s diet.

Unfortunately, the populations of prairie dogs in the North American west are on the decline. Human-related fatalities such as hunting, mass poisoning, and habitat loss affect population numbers, as well as climate change and drought. However, one of the major factors in the decline of prairie dogs is plague (yersinia pestis), the same bacterium that caused the bubonic plague in humans. When a colony of prairie dogs is struck with the plague, transmitted by the bacterium on fleas, up to 90%-100% of the colony can die. The fleas collected during the processing of these translocated prairie dogs are tested for this bacterium.

Translocation of prairie dogs is just one part of the park’s three-prong approach to boost and maintain populations of Gunnison’s prairie dogs. Park staff also search for new colonies, map existing colonies, dust existing burrows for fleas to reduce the vector of the plague, as well as distribute an oral vaccine to colony burrows.

What's Next for the Project

Park scientists are happy with the results of the summer 2022 translocation project and are looking forward to continuing their three-prong approach to boost the park’s number of Gunnison prairie dogs. In the years ahead, the park plans to collaborate with external researchers, including Dr. Loren Cassin-Sackett, whose lab at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette is looking for a genetic basis for plague resistance in prairie dogs. Park scientists are also looking to implement tools, such as radio collars, that will help them keep track of and measure the success of translocations such as these. NPF will continue to support this project in 2023 and 2024.

Related Programs

-

Wildlife

Wildlife -

Habitat Conservation

Habitat Conservation