.

.

In Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the remnants of log camps, sawmills, and company towns remain visible on the landscape. At Keweenaw National Historical Park, copper mining sites with a history spanning millennia are interpreted by National Park Service (NPS) staff and partner organizations. And, at Hampton National Historic Site, the lives of enslaved African Americans who labored in nearby iron furnaces, as well on the estate itself, have become a central focus of research and public programming.

Over the past decade, histories of work and working people have gained increasing prominence at NPS sites across the country. More than ever before, the agency is exploring the centrality of labor to American life. At sites such as Pullman National Monument and César E. Chávez National Monument, for example, union organizing is a primary focus. In the early 1890s, a strike (and later boycott) initiated by employees of the Pullman Company ground the U.S. economy to a halt, calling attention to the growing wealth inequality of the Gilded Age. Roughly seventy years later, farm workers in California’s Central Valley risked everything to demand safer working conditions and higher pay from the region’s grape growers. Their actions continue to inspire labor and civil rights activists across the country.

Battlefields and other sites associated with the Revolutionary War and Civil War are also giving greater attention to labor. Interpretation examines slavery in both a national and local context, with park staff and partners connecting military and political history to the lived experiences of free and enslaved African Americans. The Reconstruction-era is also being addressed with parks, including the recently designated Reconstruction Era National Historical Park, beginning to highlight the revolutionary implications of Black freedom for American democracy.

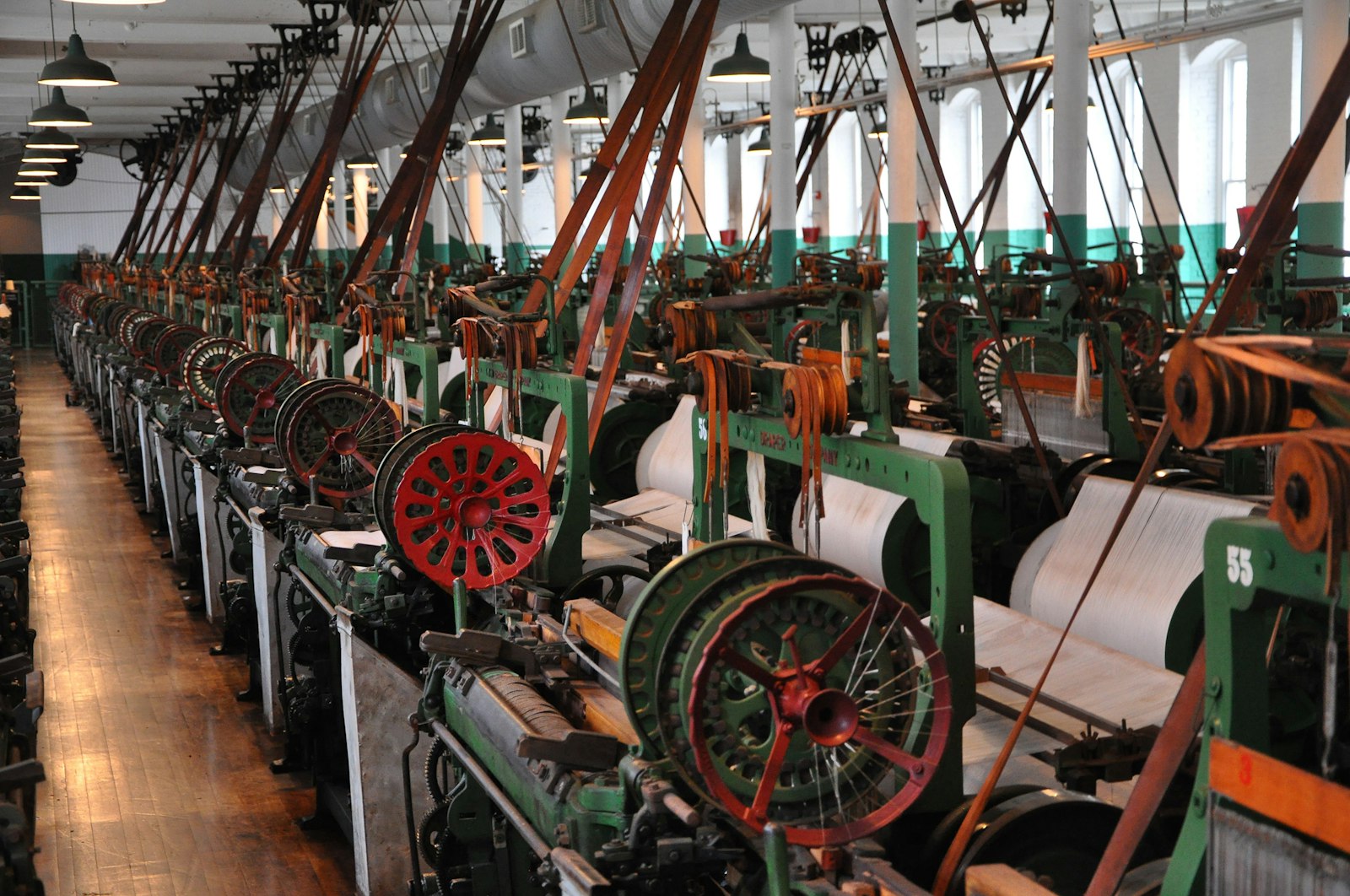

The effects of industrialization on people and the environment is also a prominent theme. Lowell National Historical Park and Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site examine the intersections of technological change and labor in New England. Both parks offer innovative curricula for young people, as well as ongoing opportunities for community engagement. At Lowell, for example, the “Workers on the Line” program challenges students to consider what they would do when confronted by wage cuts and unsafe working conditions on the job. Educational initiatives at Saugus highlight the disparate effects of early industrial production on Native and Non-Native peoples.

NPS staff are also taking a lead in researching labor history. At Monocacy National Battlefield, as well as Hampton National Historic Site, agency staff are working closely with scholars to engage the descendants of enslaved families, free African Americans, and slaveholding families to more fully understand the implications of bondage and freedom over time.

Ongoing projects at Keweenaw National Historical Park and Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park shed light on the lives of workers employed in the copper and early aviation industries respectively. These efforts are informed by both textual and physical evidence, a unique aspect of the place-based scholarship so central to the NPS. Moreover, the histories connect the jobsite (a mine or a factory) to the broader community, demonstrating that workers’ lives and interests extended well beyond the shop floor.

Every national park has a labor history to tell. This includes the work completed to create and sustain parks over time. Buffalo Soldiers played an important role in park management during the 19th and early 20th centuries, for example. Later, during the Great Depression, dozens of parks hosted Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees, who collectively transformed the nation’s protected areas. During the 1960s War on Poverty, the Job Corps program sent young men and women to parks to undertake conservation work. All these stories, along with the labor histories of NPS employees, merit further recognition.

Have you visited a park not mentioned here where labor history was interpreted? What ideas do you have about ways NPS can expand its interpretation of work? What labor history stories are important to you? Share your ideas below about how national parks can highlight the lives and experiences of working people now and in the future.

Eleanor Mahoney was the National Park Service Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow in the History of Labor and Productivity. She earned a PhD in U.S. history from the University of Washington in 2018. Her research examines the intersection of economic change and the National Park Service after World War II. This blog post is part of her National Park Service fellowship supported by the National Park Foundation, thanks to the generous funding of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Related Programs

-

National Park Service Mellon Humanities Fellowship

National Park Service Mellon Humanities Fellowship